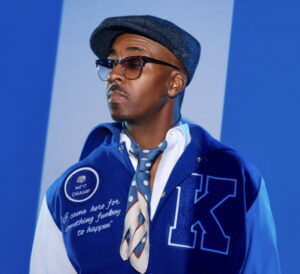

During Hip-Hop’s golden era Kwamé was a teenage phenom. He burst onto the scene and immediately made an impact. His quirky rap style, partially bleached blonde high-top fade, and signature polka dot attire made him stand out during a time when the dookie rope chain was a rap necessity. Kwamé was an innovator and trend setter from his fashion to his self-produced albums.

After releasing a handful of albums, the Boy Genius played the background producing hits under the moniker K1 Mil for artists like Will Smith, Method Man, Lloyd Banks, and LL Cool J. Thirty-one years after his last solo album Kwamé is back on the microphone with a new album called “The Different Kids.”

The Different Kids is a 16-track album courtesy of Kwamé’s Make Noise Recordings label. The release is full of Kwamé’s off-center approach, with a modern and mature delivery. The project features appearances by Vivian Green, King Pleasure, Zeus, Zacarra, and Lady Tigra.

The Real Hip-Hop talked to Kwamé about his return to rap, the realities of adulthood, why he won’t cater to kids, and his new album, The Different Kids.

TRHH: Why’d you pick the mic up again after over 20 years away from emceeing?

Kwamé: Well, you know what, I don’t want to say that I picked it up again because I think over the last 20 some odd years I’ve always been recording. I’m always saying to my friends and family, “I’m making a new album,” and I don’t never do it. I just keep recording, recording, recording, recording, recording. I think music deserves a reason and a lot of times people’s reasoning for putting out new music is to A, stay famous, or B, act like they need a comeback, or C, to make some money. To me that’s not a reason enough for me to do that. For my creative expression that’s not the reason.

So, then a couple of things lined up and started happening that made me say, “All right, I may need to say something.” It’s like an instant ‘see something, say something’ type situation. And not in any particular order but when the 50th anniversary of Hip-Hop came around, Hip-Hop is such an integral part of my being, knowing it from its public beginnings and stuff like that. So, when people started getting recognized and honored I was like, as long as they stick to people like Melle Mel, and Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash, and the founders that probably didn’t get to reap the benefits of a lot of stuff that a lot of other rappers got, stick with that, I’m fine.

I didn’t want to be a part of any of it to be honest with you, and I wasn’t. But I started seeing exhibits; I went to the Smithsonian exhibit in the African American Museum and the whole upstairs is like a music exhibit on the top floor. It’s the history of black music and then it gets to Hip-Hop, and then it gets to Hip-Hop fashion and all that kind of stuff and there’s all these rappers names on the wall. I’m like, “Dag, they couldn’t even put my name on the wall? Like, I didn’t do nothing? Even with the clothing?” I was like, “All right, I’m not going to say nothing.”

Then there was another exhibit during the Hip-Hop 50th where they said, “Hip-Hop Fashion 1988 to 1991” or something like that. I was like, “Okay, I know what was going on in 1989, I know what was going on in 1990, and I know what was going on in 1991.” I know what all the kids was wearing and I know what most of the kids was looking like, let me go check this exhibit out. It looked like somebody just took an eraser to everything that I did. It was just not anything and I’m not asking for the acknowledgement or the recognition, but I’m like, “Dag, we’re talking about history.” For example, it’s like American history and not saying the Native American was here. You can’t not say that.

So, part of me started getting upset like, “Ah man, they trying to hate on me!” And then I was like, no, let me not do that because that’s not my being — I’m not that kind of guy. I thought about it and I was like, this is like a room full of children in school and the kids are jumping up and down, and making noise, and the teacher comes in and they’re talking, and the kids is raising their hands ‘pick me, pick me’ the kids are expressing that they want to go to lunch, the kids are saying they want to go to the bathroom. They’re being kids and they’re expressing themselves and they’re getting chosen, but then there’s one kid in the corner that’s just reading the comic book or reading their book, not participating, not saying anything, not expressing, and then wondering why the teacher never picks them for anything. I’m that kid in the corner.

I’m like, “You know what? You got to stop being that kid in the corner.” And that was a life lesson that I had to learn later in life. Stop being the kid in the corner. A closed mouth don’t get fed and a non-expressive person doesn’t get recognized. Like I said, I’m not doing it for the recognition, but if I want to remain in the room I need to express myself. Now, I could remove myself from the whole thing and just say, “You know what? I’m good. I did what I did, I served my time, I’m out.” But if I chose like I’m choosing to remain in this room of Hip-Hop, I need to express myself.

Especially when I know that I still have credible beats, I still have something to express lyrically, and I can express it lyrically and not sound like I’m struggling, I need to do that, because if I don’t do that the only person that I failed was myself. You never want to go through life, or go through later life, feeling that form of regret or feeling that just as a person you could have just done more. You could have said more, you could have expressed more, you could have created more, whatever it is. So, that was the initial battery in my back like, “Yeah, y’all ain’t just going to have me sitting in this corner while y’all jumping up and down and getting Happy Meals, nah!” So, that was mostly it.

TRHH: You mentioned being the kid in the corner; is that why you titled it The Different Kids?

Kwamé: Yeah, because that was me my whole life. I dress different, I act different, I listen to different music, I express myself in a different way, and it’s like society tells you, you can’t do that. Society tells you that you have to be just like everything and everyone else. I’m here to say, “Nah, nah, nah, nah, nah.” This is unapologetically me and when you’re unapologetically you it cannot fail. It can’t fail.

No one can say, “I don’t like you because of your ears.” What you talking about? I can’t change my ears, like what the hell you mean? And you can’t even be mad at that. That’s the same thing with doing the music, it’s like, nah, I’m just going to do me and express myself, and hopefully there’s someone out there that feels the same way and understands what I’m doing, because I’m representing for those people.

TRHH: One thing I love about The Different Kids is how it’s not too short, yet not too long. Was there a concerted effort to cater to the short listening span of the listener while still giving the album heads some joints?

Kwamé: Yeah, because people consume music by swipes on a phone. Thirty second swipes, fifteen second swipes, one-minute swipes, and we have been trained as a society now to consume fast food. So, my thing was, let me cook some home cooked food in small portions. You could pack it up and take it with you and if you want some more you could listen to it again, you could ask for seconds. So, yes that was a concerted effort, and at the same time it’s like, I ain’t been around for 26 years in this form. I’m not about to sit up, post on your couch and talk you to death either. I’m saying, “Hello, I’m here, I’m back, nice to see y’all, I hope you enjoyed this, thank you, come again.”

Hopefully people listen to it again and they get the messages that I said, because the album is 27 minutes but I’m packing it. It’s packed. I’m trying my best to not give you fluff and fillers — it’s nothing like that. Every record goes with each other and they all have a meaning behind it. There’s a deeper layered meaning to everything that I put on the album. Hopefully people resonate with that, even if it’s their tenth listen and they start to unpack what I’m trying to give them.

TRHH: On the song “Hello/Anybody?” you say, “I hope it’s not too late for my kinda, lyrical dire rhymers, that lack drama/Instead of selling black trauma, disrespect black mama’s, or pack llama’s.” Woo! How worried were you that you might not have a place in today’s Hip-Hop landscape?

Kwamé: I don’t think about it. I’m not even worried. It’s like saying I built a hut in the middle of the forest and then someone asked me, “How worried are you not having an apartment in the middle of West Loop?” I’m here in the forest! I ain’t thinking about West Loop, I’m like right here [laughs]. So, that’s how I feel about it. I don’t even think about it because it’s like, I want to make sure that I am 100% authentic, and I want to make sure that if you do like it, all I ask is for you to tell the next person and let them listen to it and judge it for themselves. I think from that point your place will be solidified whether you tried to do it or not. I may not even see my place, I might not even be on this earth anymore and where my place is solidified and fit in. I don’t know. All I do know is I just gotta create.

TRHH: Flipping the Diff’rent Strokes theme on “Stroke Dif’rent” was genius. What made you decide to chop that song up?

Kwamé: Thank you. Well, I always wanted to mess with that song. In different ways I always sampled and played with this song, but there’s a DJ program called Serato and in Serato it allows you to remove vocals and different instruments on a track. So, when my DJ was showing me how to use it the first thing I grabbed was the Diff’rent Strokes theme just fooling around. I separated everything and I just played the drums. I was like, “Oh, I can rhyme off of this!” As soon as I heard them drums I hung up and I was like, “Yo, I’m making a song!”

I made Stroke Dif’rent right then and there and that was the song once I played it where I said, “This is my album.” That was the jump off point and then I made the album based on Stroke Dif’rent. I wasn’t going to do an album full of TV show themes, but Stroke Dif’rent to me is raw! It’s like extra raw — there’s no hand claps, and synthesizers, and people singing, outside of the theme song. I wanted to keep the album that way and I said, “This is how I want my album to sound and this is where I want to go.”

TRHH: Were you worried that younger kids wouldn’t get the reference?

Kwamé: I wasn’t thinking about the kids. I ain’t think about no kids! Seriously. I’m not. You ever a sit with your friends and you’re talking, you’re worried about them picking up something they’re not supposed to pick up, but when you’re just having a conversation you’re not thinking about if they understand what I’m saying. I’m speaking to my friends, I’m speaking to my peers, I’m not selling to a 15-year-old. If I wanted to sell to a 15-year-old I would find a 15-year-old rapper to make the music for and let them sell it to the 15-year-olds. I’m not doing that. I think that Generation X has been severely overlooked in the Hip-Hop space – severely. Radio won’t play any of our artists records.

We got one station, Rock the Bells, and that’s the only station that plays any of our stuff. I don’t know how much old or new stuff they play from these artists, but a lot of artists from that generation are making records. I just want to speak to that generation unapologetically. Think about it, when you’re a kid and you overhear your parents talking, your grandparents talking, you act like you’re not listening, but you’re listening. And maybe there’s a parent playing The Different Kids and their teenagers listening and might tell their friends, “You know, I heard this record.” You never know. I don’t know yet. I haven’t gotten that feedback yet.

TRHH: You mentioned Serato; what’s in your production workstation?

Kwamé: I mix my stuff up with a lot of things. I never get rid of my old Akai MPC 2000XL. That is the brain. People are like, “Why are you still using that?” Because it works! What are you talking about? I’m able to achieve anything. It’s a tool that I know how to use very well. Then I always incorporate live things. I don’t like someone giving me sounds. I want to make my sounds. All my sounds I tailor make outside of a classic sound like an 808 or something like that. But a snare, a hand clap, a finger snap, or whatever it is, I got to make the sound. I could use the same hand clap on everything, but I’ll be doing 12 tracks of clapping and sample that clap. It’ll take me a little bit more time to probably make a beat more than probably the average newer beat maker, but I gotta incorporate that.

I gotta incorporate live instruments. If it’s a bass, or guitar, or horn, it has to be a real person. Or a string instrument like a violin section; I may play it at first, but I gotta bring somebody who plays it for real in. And it’s not to say, “Oh, I got live horns and live strings!” Sometimes I won’t even put it down that I did that. For me I need to hear that. I need to hear my work being done by a human besides myself. It adds a layer and a nuance to my production that I think kind of sets my production to the side than from somebody who’s using Fruity Loops or whatever they’re using, I don’t know, they could be using whatever.

TRHH: I saw you perform in 1989 on the Straight Outta Compton tour.

Kwamé: Oh, okay.

TRHH: That tour was recreated in the Straight Outta Compton film; what are your memories of being on tour with N.W.A, Too $hort, Kid ‘n Play, J.J. Fad, and The D.O.C.?

Kwamé: That was the greatest two weeks of my life. I’m not even gonna lie. Maybe it was 3 weeks? Maybe not the greatest, but of my life moments that is a highlight of the life moment. A, because it was probably the first tour I was on, but B, it was the fact that for the first time, and maybe for the only time, I don’t know, but it was just about Hip-Hop. This is before anybody started beefing about West Coast and East Coast and Midwest and Dirty South. It was not separate. It was just kids doing Hip-Hop.

And on top of that, because of NWA’s record “F the Police” we had to go to major cities with no security. Every police department boycotted the show. So, we had to play 30,000 seat arenas, 20,000, 15,000 seat arenas with no security. So, a lot of times we had to go to cities and go under aliases. And it was funny because I’m on the tour, Kid ‘n Play is on the tour and we’re the least gangster on the tour, but we were caught up in the gangsta stuff. Cops would show up at the back of the stage, and they show it in the movie, like, “If you say this, if you do this on stage you’re immediately arrested.”

But what they didn’t show in the movie was Eazy-E sitting myself and Kid ‘n Play down like, “Look, even though it’s our tour we can’t go on last in every city. So, we’re going to go on second to last, third to last. We’re going to do all our crazy stuff and then we’re all going to jump in the audience and run out the front door while the cops run on stage trying to arrest us.” But what happens is so Eazy jumps in the audience and I get on stage immediately. No introduction, I just get on stage and just start rocking. Kid ‘n Play just started rocking. By the time the cops come they see Kid ‘n Play on stage, where’s Eazy-E? Where’s N.W.A.? They’re gone. They’re already in the van.

So, that experience, there’s a movie made about these people, but for me and my brain, we were just kids doing stuff. We were just kids hanging out on tour doing what we had to do and it was all Hip-Hop. It was Hip-Hop that I was introduced to for the first time ever. I knew N.W.A., I knew Ice Cube, I knew Eazy, but I didn’t know who Too $hort was until I got on tour. And to see Too $hort get on stage and 30,000 people know every single word, ‘cause New Yorkers did not play West Coast music. It was just banned, we were not playing it.

So, to be on tour with these people, The D.O.C. before anybody knew who he was, J.J. Fad, people became more like a family and friends. There’s people from that tour that I speak to, to this day. And that’s dope. I’ve never seen that again on a tour, because then it became the Native Tongues tour, the East Coast tour, the Lyrical tour. It turned into the compartments and that aspect of Hip-Hop is lost. They don’t do it anymore.

TRHH: It is. There was a there was a tour a couple years later that I went to that was diverse like that with Public Enemy, Geto Boys, Fresh Prince, Naughty. But that was like the end. And now it’s like so segregated and separated. We can’t go back for some reason. We need that diversity back, because there’s something for everybody on a show like that.

Kwame: Yep, yeah, yeah, I know. I was on that tour on certain dates as well. When you put classic Hip-Hop and just classify it as “classic Hip-Hop” we didn’t have to like everything. Say for example, I didn’t buy say a particular artists album, but I recognized the one song that I liked. I didn’t have any problem with this one over here, I like that song, and I like this one’s song. That diversity, that’s just how we were in general. We didn’t like all flat out hate this type of rap, or hate that type of rap, or hate this rapper until we were told to! We were literally told to hate the different rappers from different places. “Nah, West Coast, nah, East Coast, nah, Chicago, Atlanta!”

Why did we do that? We kind of did that to ourselves. I don’t know if it could get back to it or not, I just know with The Different Kids I try to speak to everybody from that generation. I’m not running up and down on the album, “Queens, New York!” I’m not doing all that. You know for the longest time most people didn’t even know where I was from, because I was about trying to bring everybody into one space. So, hopefully at least our generation can get back to that. At least they should focus towards our generation that is diverse like that, instead of just one thing.

TRHH: “Adulthood” is a grown-up song. How much of that was based on your personal experience?

Kwamé: 100%. But based on personal experience or personal experiences of people very close to me and I just mixed people together and changed the narrative. It’s things that actually happened, and things that actually happened to me, and things that happened to close friends. A lot of people my age, especially the guys I know, they super resonate with that song because it’s about not being in one place as an adult. You might grow out of something and if you’re with somebody and that person is your partner they may grow further than you and expect you to grow with them.

You may want to, or you may not and you got to understand what the consequences of that is. That’s what adulthood is. It’s not just being older, it’s dealing with the changes of life. Because kids, they’re in a world that’s just that world. They don’t understand the change, but when you’re an adult you start to see the change in hyper time. Lifestyle change, health change, wealth change. There’s a lot of people in our age group that get left behind because one of the spouse members can’t do it, they can’t move, or they’re moving too fast and leave you behind.

Especially that second verse for me is very autobiographical, because it was like, “All right, I’m stuck in this space, my woman is carrying the load, she’s giving me advice, I’m not listening, so, it puts me deeper in a space. But I’m deeper in space and I’m stuck in a space because I’m depressed and I don’t know it. So, the thing I’ve decided to do is pick up the family and move somewhere else and hopefully that can jump start a better life. And I gotta win. I gotta win because I removed my family from their habitat to be able to win.”

That’s adulthood. People face that whether it’s across town, whether it’s across the country, it could be across the world. Sometimes you got to make that decision. I don’t think a 20-year-old could ever come from that perspective. They can only come from the perspective of, “My dad moved us to such and such,” and they’re mad about it [laughs]. So, that’s about it.

TRHH: “Kwamé 2 Kwamé” is an interesting song where you’re giving yourself a warning. Do you share the lessons you’ve learned with younger artists, and if so, are they receptive?

Kwamé: I don’t know if they’re receptive, but I do share. And I try to share from a point of not trying to tell them that my way was better, or my time was better. I say this to them, “This is what happened to me and this only happened to me because no one told me what I’m telling you.” You know how you kids are. You could tell them, “Don’t jump off of that you’re going to get hurt,” and they looking at you like, “What do you know?” “Don’t jump off of that couch, you’re going to hurt yourself!” Bam! You know what I’m saying? It’s like, “Hey, I told you!”

And that’s life, so when I speak to younger artists that’s what I do. I’m telling you what happens. This is the music industry. This is the one industry that has not changed since 1958. You could say, “They’re streaming now,” it’s the same beast in a different coat. I’m telling you what’s going to happen. I can guarantee. I don’t care how famous you are. You could be Drake, you could be the guy they ain’t never heard of before, I’m telling you I know exactly what’s going to happen. Take it or leave it, and that’s all you can do.

TRHH: Who is The Different Kids album made for?

Kwamé: The Different Kids album was first made for me. It was my therapy, it was my self-expression because I felt like I was lying to myself. I felt like I’m calling myself an artist and a producer and I am not producing art. I cannot do that. I cannot call myself one thing and be something else. So, if I’m going to say I’m an artist/producer I need to produce some art for myself. I’ve been doing it for other people. I’ve been working for other people for 25 years. I’m doing myself a disservice, and while I’m able to do it and I’m able to do it on a high level, I need to do it. So, that’s who the album was for.

Then after that, the album is for the people from my generation that may feel the same way or that may need that push. Because they tell us in society that over 40 you don’t have a thought, you don’t have a belief, you don’t have any skills, you are not viable in any workplace whatsoever, and you’re no longer useful, but give us your money. I made the album to say, “Look, if I’m doing it, so can you.” Whatever it is. If I can pick up and decide to do something again at a high level, so can you. Whatever that thing is. And we’re not talking sports. I’m not telling you at 50 to go out and become a football player, no, that doesn’t make any sense. But if you have a mind and an idea, you could do whatever you want that’s based on that mind and that idea. So, that’s really who the album is for.

It’s not for the radio, it’s not for quick consumption. It’s an album to listen to, an album to vibe to, an album to unpack. You may like two songs today, five more songs tomorrow, a third song that you never even thought about the next day. It’s for that and hopefully you get the lessons. This is another thing that’s important; this is the first album I’ve ever made where I’m not playing games. Every album I ever made I was playing games. Like, “I can do this, I’m just playing with y’all,” literally. “I’m just playing with y’all. I could do more, but I’m just playing with y’all.” And this time I was like, “Nah, I ain’t playing with y’all.” I’m not playing with you. I’m trying to tell you something. I could be doing it in a playful way, but I’m really trying to tell you something and I’m really trying to show you something. Hopefully you get it and you receive what I’m trying to give you.

Purchase: Kwamé – The Different Kids