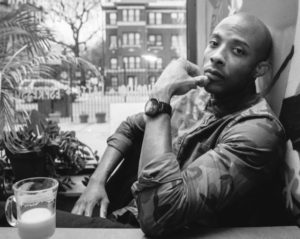

Chicago based emcee Pete Sayke has returned with a new album called “Gold & Rue.” The ten-track release finds Pete tackling tough topics over jazzy back drops. The Cincinnati born rapper uses his signature Midwest flow to speak on piety, poverty, and philanthropy, among other topics.

Gold & Rue is produced by Mike Jones, iLL Brown, LONEgevity, Theory Hazit, Dreamlife Beats, and Phoelix. Released by Fantasic Sound, the album features appearances by Phoelix, JusSol, Mother Nature, and Roy Kinsey.

Pete Sayke spoke to The Real Hip-Hop about the catechization of his own faith, basketball icon Michael Jordan and his philanthropy, or lack thereof, and his new album, Gold & Rue.

TRHH: Why’d you call the album Gold & Rue?

Pete Sayke: Gold & Rue is a play on the golden rule; do unto others as you would have them do unto you. A lot of my projects have this underlying theological theme. I’ve always kind of struggled with that idea; whether or not it’s real, what happens, that kind of thing. It’s always an internal struggle of sorts. Some of my latest readings had me go down that path. I wanted to kind of examine that. For my life I wanted to break it down. The gold represents all of our aspirations, whether it’s financial or any kind of recognition. The rue means regret. It’s all of the stuff that we sacrifice in order to get to those things, whether it’s time with family, friends, our own health or sanity. I wanted to look at different points of my life from childhood all the way up to adulthood and break down how I’ve struggled with it and how I watched people around me struggle with it.

TRHH: The overall vibe of the Gold & Rue is a positive one. It feels optimistic. Would you say that’s a fair assessment?

Pete Sayke: You know what, I think that I would like it to be that. Even though I tell these stories, and they’re all true stories, about friends of mine that are locked up or dead, there’s always a tenor of, “but it doesn’t have to be you.” I am that. It’s almost like a good kid, M.A.A.D City type of thing. I’m not saying by any means that Cincinnati was like Compton in the 80s. Seeing the people that I was around deal with what they dealt with I was luckily able to recognize how fortunate I was to have both of my parents at home. Even though I had both of my parents I was fortunate to have them both actually care about me. All these things that I was set up for allowed me to learn from others mistakes, even though I did make some myself and it led to certain things happening in my life, I’m still here. I guess that’s the optimistic part of it. So yeah, it is a good balance of a harsh reality and also you don’t have to be that person either.

TRHH: How would you compare this album to your last one, Heaven Can Wait?

Pete Sayke: Heaven Can Wait was like, “Holy shit, there is so much happening politically and socially, I need to speak on it.” Even the sound of it was urgent and immediate. There was a lot more rapid-fire bars – it was visceral. With Gold & Rue it’s a little more internal and not in a religious way, but it’s a little more spiritual. It’s meditative almost. That’s the way I kind of look at it. Approaching it that way, I sat down with Mike Jones and we crafted a jazzier, little more soulful vibe as opposed to what LONEgevity and I did. It’s hard for me to elaborate on that right now. What would you say is the difference to you as a listener between the two projects?

TRHH: I think this one is definitely more optimistic, like I said earlier. It seems like you played with the flows a little more on this one. I haven’t listened to the last one in a while, so I was curious how you viewed it and where you were between the last project to Gold & Rue.

Pete Sayke: I remember performing songs from Heaven Can Wait and I was heavily relying on my DJ. I was running out of breath [laughs]. I needed to change my approach on the next project. Even if I had double time bars, I wrote things specifically so I could perform them. That was one conscious decision that I made, and it just happened to coincide with the decision to go the jazzier route.

TRHH: You mentioned the religious elements of your music; what is your religious background?

Pete Sayke: Currently, I’m just a human trying to exist. I’m not tied to anything. On a daily I try to practice the ideals of Buddhism, but that’s more practice than a religion. I was born into Catholicism. I was raised Catholic, I want to catholic school from K-to-12. It’s kind of like the predominant religion. I explained this in a song I did for the group Grumpy Old Men for a song we did on our Sunday Skool album on a song called Sunday Skool. I kind of break down my thought process from being forced to go to church all the time in school and then being forced to believe this, but along the way being like, “Oh, all this crazy shit is happening in the world. All these religious leaders are scamming people out of bread. Oh, all these priests are fondling and raping kids.” That’s one of those things where you can’t make a blanket statement like, “Because all this happened Catholicism is fucked up.” As an adult with my own brain I have to examine what’s real to me and what matters the most. Then it ties in to Gold & Rue. That’s the way I feel like we should live. If everybody focused on trying to be kind and compassionate and look at it through those optics, I think we would be much better off. Everybody wants their team to win all the time.

TRHH: On the song “Heirs” you are critical of Michael Jordan for not being more of a voice to people in the community. Not to defend MJ and his charity or lack thereof, but I would argue that Jordan is from a different, more comfortable generation than athletes like Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown, or even LeBron James. Jordan and Charles Barkley were in the same draft class… did you happen to see the video going around of them on Oprah?

Pete Sayke: No.

TRHH: There is a video of Jordan and Barkley on Oprah from the 90s. In the video Barkley is saying he tried to give a homeless man some money and Jordan told him if, “If he can ask for money he can say, ‘Welcome to McDonald’s, may I take your order?’”

Pete Sayke: Bomani Jones is one of my favorite sports personalities. I remember him alluding to that story. That was the first time I’d heard that. I’ve heard so many other ones, that’s why I mentioned that in the record also.

TRHH: It’s being painted like Barkley is a good guy and Jordan is a bad guy, but they’re very similar people. They come from a similar era and Barkley famously did the commercial saying he’s not a role model. What’s your take on that viewpoint that these guys are just from a different time?

Pete Sayke: What you just said is something that I even have to evaluate myself. We always bounce ideas off of each other – me, Mike Jones, and Roy Kinsey. In our group thread I’ll send a voice note like, “Yo, what do you think? They were really critical, but not in a negative way. It was more like, “But what about this?” For me it was kind of like what Michael Bennett said on LeBron James’ The Shop where he said, “Even back in the 80s and 90s things were bad.” Even if you just look at Chicago, I wasn’t born and raised here, I’ve only been here for ten years, but Chicago has a powerful history — it continues to today.

You have the single strongest person in all of sports, especially at the time, you don’t have to do a ton. I even say it in the song, “Nobody is expecting you to be Jesus Christ.” Once in a while when kids are getting jacked for their shoes can you just say something? You’re the most powerful person in the city – you and Oprah. Before I get further into that, let me just say I didn’t write the song as an indictment necessarily. I wanted to write a bunch of allusions to the idea of Michael Jordan. I think what’s important is that everyone is held accountable, not brought to task and put on the guillotine. You’re allowed to not have to feel like you’re a role model. Nobody should be able to tell you anything.

A few years ago, when LeBron, Wade, and Melo were at the ESPYs saying we have to do better and give back to the community, after I think Jordan felt the pressure and put out a statement and gave a million to some charity and a million to the police and was like, “I can’t sit quietly anymore.” Anything is good, but I wondered, “Why are you doing this right now?” For 30 years you didn’t give a shit and suddenly you’re like, “The biggest athletes in basketball are making me look like shit. I can’t be quiet anymore,” but you really haven’t said anything since then. It’s not supposed to be all about him, but when you think about athletes or entertainers or anybody, I think MJ is arguably the one that most people go to when you think of the greatest. Would you say so?

TRHH: Yes.

Pete Sayke: Right. So, I wanted to use allusions to MJ to kind of represent all of us. That’s why I was like, “I’m short and I probably won’t go to the league, so I have to figure out a way to get what he’s got.” In one way these athletes are inspirational, but it’s also a double-edged sword. The people who are role models locally, like parents, aunts, and uncles, if they don’t have the tools to show us how to get there, then all of us are just searching blindly. Does that make sense to you?

TRHH: It does. I’m not necessarily on being positive about Jordan. I just wanted to kind of play devil’s advocate. I do believe partially that it’s a generational issue, but 100%, that guy is about his money. A guy I know recently told me he went to Kenya and met with Barack Obama’s grandmother. He asked her, “What can black people in America do to get out of the situation we’re in?” and she said, “You have to stop following white western values.” It blew my mind. He went on to talk about how we value money here. Everything is about money.

Recently I had a conversation with a friend and I told her that I was going back to school to get my Bachelor’s Degree at 43 years old. She asked me why I would do that if I already had a job. She asked if it would help me make more money and I said, “Not really, it’s just something I wanted to achieve for myself.” She said it was a waste of money. It hurt my feelings, but that’s how we are. If it’s not going to help your bottom line, what are you doing? That’s our society and that’s Michael Jordan. So, when you say the line, “Republicans buy shoes too,” he’s not going to fuck up his money in the 80s, the 90s, or now. I’m glad you made the song. I just wanted to throw that take out at you.

Pete Sayke: It’s funny because that’s why Mount Mutumbo comes right before that. Two people from that same generation, obviously from different backgrounds, but approaching life completely differently. That could be because Dikembe didn’t follow that western white culture. He continues to be not only a great philanthropist, but a great humanitarian all around. That’s not to say that Mike doesn’t do anything.

TRHH: From his position he could have and still can do a lot more. That’s the situation.

Pete Sayke: Exactly. It’s hard because this is just my perspective. A book that I’ve talked about ad nauseam is Eckhart Tolle’s “A New Earth.” One of the big takeaways from that book is trying to eliminate ego from every thought and every conversation. I realize that me expressing myself on this song can come off egotistical or like I have the answers and it’s not. I don’t. I try to write some of it from the way I felt when I was a kid, all the way up to now. I remember thinking that a little bit coming up like, “Damn, man. Why can’t Mike bring the price down?” or “Why doesn’t he buy some for everybody in the inner-city?” That’s what I thought. “Maybe people wouldn’t kill for these if he just said, ‘You guys, stop it.’” That’s just an example of something that he could do. I don’t have the answers, but it creates a debate. Even among me and my best friends. It got a little heated, but it’s an important conversation to have.

TRHH: Another song on the album “Climbing” sounds like you’ve thought a lot about your own mortality and judgment. What inspired you to write that song?

Pete Sayke: I started going to therapy in January. I started having a bit of an existential crisis. It reached its peak this winter, but over the last year, year and a half when I started to write this project, I was thinking about the songs on this album. Any time you think about topics like this it takes you to certain places. I think that me realizing that we’re all going to die, then my wife’s aunt passed away, and three weeks later my aunt passed away in December, looking at my parents being as sick as they are, and looking at my age I just started to go down this rabbit hole. What’s important? I have to figure this out. The time we have is so important.

I wanted to write Climbing from a couple of different perspectives. The first verse is about a normal good person. It’s almost written from my perspective as a rapper. I’m spending my time as a mortal trying to be immortalized. I want all these people to remember me, but inevitably it doesn’t matter. I’m going to be gone and the fact that people remember my legacy doesn’t matter. It won’t affect me. I’m not going to know that people care. The second verse is somebody who looks at it completely differently. They have everything, they’re balling out, and they’re trying to protect what they have at all costs and then they get to heaven and God is like, “You know you can’t take your wealth with you. That was kind of stupid.” It was all born out of my anxiety, which I’ll probably delve into on a future project or something.

TRHH: Have you found therapy to be helpful?

Pete Sayke: Yeah, man. I was going every single week for about a month and then I tapered it down to every two weeks. Then it was once a month, now when I start to feel anything I’ll go back in there. Some of the conversations get uncomfortable. I have to really look at myself and ask, “Why are you putting that pressure on yourself,” or “Why do you expect that from people?” I can’t really escape. I could, but what’s the point in that? I mean, I could get up and leave right now, but that’s dumb. Now you’re forced to answer to yourself. It’s funny because everybody could benefit from it. Everybody needs somebody to talk to, but sometimes you need somebody to talk to who isn’t biased toward or against you. You say what you need to say and not feel judged, not feel like you’ll hurt somebody, and not feel hurt yourself. It’s good that it’s not such a taboo anymore, especially in our community. I guess we’ve got to shout out Jay-Z for making it a little more popular. One of many people to shout out.

TRHH: What do you hope to achieve with Gold & Rue?

Pete Sayke: Every project moving forward, I just want to make black box music. When all civilization fades away and all they have is to look at artifacts, I want people to be able to learn something about me, us, the time, and the spirit though my music. That’s it. I just want my music to resonate with people. I want people to hear Gold & Rue and feel like they can see themselves in some of these stories, see people they know in some of these stories, and like you said, feel optimistic. You can fuck up ten times over, but change starts today. If today you’re like,” I need to move in a different direction,” you’re already moving in that direction because you said you wanted to. That’s what I want. I want people to really feel this music.

Purchase: Pete Sayke – Gold & Rue